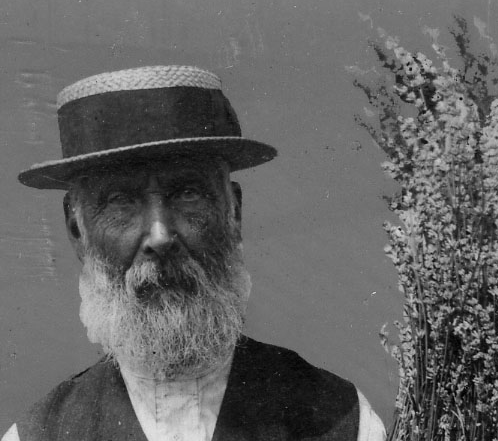

Lavender grower who lived at Lavender House in Bond Road.

He had a stall at Covent Garden from 1882 to 1919, according to this article in the Hull Daily Mail of Monday 28 July 1919:-

Sweet Lavender.

Mr Henry Fowler, one of the largest dealers lavender in the country, who has large gardens at Mitcham, has retired from the Covent Garden stall which he has occupied for 37 years without a break. The first crop of lavender from Carshalton was cut on Saturday, and a few bunches were on sale in the streets.

After the First World War, the price of lavender had doubled, and was grown outside Mitcham, according to this article from 1920:

Mitcham Lavender Dearer.

The first cut of Mitcham lavender, which is ready for market a fortnight earlier this season, has been made by Mr Henry Fowler, of Lavender Nursery, Bond-road, Mitcham, known as the last of the growers. –

It is 1s 6d a bunch this season, which is more than double the pre-war price. The crop, though small, is in fine bloom. Most of it is grown just outside Mitcham, at Wallington and Carshalton.

From the West Sussex County Times – Saturday 17 July 1920.

In 1921 the price was five times that before the war, he said in this article from the Daily Herald of Monday 18 July 1921:

SWEET LAVENDER

Once Flourishing Trade Now Almost Extinct

For the first time in Mitcham’s history, the lavender season has opened without even a sprig of the sweet-smelling plant being on sale in the town.

“It doesn’t pay to handle it nowadays,” said Henry Fowler, well known at Covent Garden as “the last of the Mitcham lavender kings,” to DAILY HERALD representative, “although never do I remember such a figure it fetched in Garden yesterday — 20s. a bundle. Before the war I sold for 4s.!”

Mr. Fowler, who is 76, used to sell as much as 20 tons a season. All the “Mitcham lavender” (offshoots from the original Mitcham stock) is now grown at Carshalton, a neighbouring place, by a Beddington firm of market gardeners.

There are only about five acres left, but next year, Mr. Fowler said, there would be more grown. “And then I shall dabble in it again.”

Mitcham soil grows the finest lavender in the world, but the market gardeners say that other flowers and vegatables are more profitable. Moreover, all the land will soon commandeered for manufacturing purposes.

Distilling lavender is still a big trade in Mitcham, much of the plant coming from Hitchin, Worthing, and other places.

“It is the first time for 40 years I have never had lavender to sell,” were Mr. Fowler’s parting words.

A large lavender distillery was run by W.J. Bush & Co. Ltd.

Henry Fowler had been born around 1846 in Dunstable, Hertfordshire. When he was 35 he was a florist’s labourer according to the 1881 census, which shows him as living at number 6, Dixon’s Cottages (near the present day Gardeners Arms in London Road). In the 1911 census he is listed as a florist, aged 65, with his wife Anna 72, and daughter Nellie 39.

He died in 1925, as reported locally and in the West Sussex Gazette – Thursday 26 March 1925:

Mr. Henry Fowler, the “Lavender King,” hes died. For over 40 years he supplied Covent Garden market with big consignments of lavender. Since 1922 he had been out of the business.

Note that lavender is still grown in Carshalton.

News articles are from the British Newspaper Archives, which requires a subscription.