Pub that was at 60-62 High Street, Colliers Wood, SW19 2BY. The site is now occupied by a CO-OP.

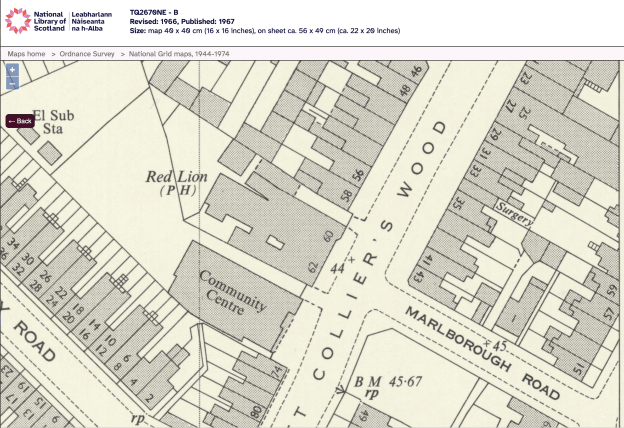

1967 OS map. Ordnance survey maps are reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland (reuse CC-BY).

Licensees

1972 – Dennis Callaghan (source: Mitcham and Colliers Wood Gazette 22nd June 1972)

1925 – Mrs. J. O’Neill

1902 – Ellen Kettle

1896 – Samuel Ezekiel Kettle & Mrs. Ellen Kettle

1875 – John Marchant Penfold

1870 – James Marchant Penfold

1867 – Mrs. Maria Chandler

1851 – James Townsend

1837 – Henry James Hoare

1824 – William Pithouse

1822 – Ann Ritchie

Disco Pub

In 1972 owner Charram Ltd, part of brewery Bass Charrington, converted it into a disco pub.

The Battle for Collier’s Wood: How a “Mind Blowing” Disco Pub Sparked a Residents’ Revolt in 1972 LondonThe conflict is timeless: a new business opens, and the quiet rhythm of a neighborhood is suddenly disrupted. Disputes over noise, parking, and a new crowd of people can quickly escalate into a battle for the very soul of a community. While these stories play out in towns and cities every day, few are as perfectly preserved in amber as the one found in a collection of 1972 newspaper clippings from South London. This is the wild, hyperlocal history of the Red Lion Disco Pub—a culture clash that pitted Go-Go Girls and groovy tunes against a residents’ association threatening “militant action.”

A New Kind of Nightlife Sparks a Fire

In 1972, an advertisement for the Red Lion at 62 High Street, Collier’s Wood, promised a revolution in local entertainment. It wasn’t just a pub; it was a “Fabulous Disco-Pub!” and “It’s South London’s latest disco!” The ad trumpeted “dancing seven nights a week,” the “Latest discs!” spun by a “Top D.J.!”, and the presence of “Go-Go Girls.” It urged patrons to “Come and do your thing!” in an atmosphere it declared both “Groovy!” and “Mind Blowing.”

This hybrid venue represented a seismic cultural shift. For a London suburb accustomed to the traditional quiet pint, the fusion of a local pub with the loud, vibrant, youth-driven energy of a modern disco was an entirely new and disruptive concept. The Red Lion wasn’t just offering a drink; it was importing a high-energy, city-center nightlife experience directly into a residential neighborhood.

“Militant Action” and a Neighborhood “Polluted with Riff-Raff”

The arrival of the disco pub was not met with universal enthusiasm. As one April headline in the Mitcham and Colliers Wood Gazette bluntly stated, the “Red Lion Pub Row Hots Up.” Residents felt “plagued” by the pub’s patrons, and their response—a blend of formal civic organizing and populist rage—is a classic example of a community reacting to perceived cultural intrusion.

Initially, the opposition was procedural. The Collier’s Wood Residents’ Association, led by its secretary Mr. Percy Whiffin, began organizing public meetings to plan their strategy. They launched a petition to have the pub’s music and dancing licence revoked, a campaign that gained significant traction, gathering nearly 500 signatures.

But as the weeks wore on, the frustration escalated dramatically. By May, the newspaper was reporting on a “stormy meeting” where residents threatened to take “militant action.” The core complaints centered on “parking, tight hooliganism and misuse of property”—the term “tight hooliganism” likely referring to drunken or loutish behavior. The strength of local feeling was captured in one resident’s fiery statement:

“We have become polluted with riff-raff who don’t even live around here. It would be a good idea if we withheld our rates or even circle the pub to stop people from going in.”

This wasn’t simply a two-sided war. The pub’s owners, Charrington, became a third party in the conflict. Mr. Wray, a general manager for the company, met with residents and assured them Charrington “had taken up the problem very seriously,” and the company put up notices inside the pub asking patrons to be quiet when leaving.

The New Manager Who Found the Chaos “Quite Enjoyable”

Thrown into the middle of this escalating war was Dennis Callaghan, the 28-year-old Irishman who had taken over as manager of the controversial pub just three weeks prior. Surrounded by angry residents and intense media scrutiny, Callaghan offered a surprisingly calm perspective on the chaos. His cheerful detachment provides a fascinating counterpoint to the high emotional stakes of the residents, highlighting the gap in perspective between the provider of the new entertainment and the recipients of its consequences.

Instead of expressing frustration, he told the Gazette he was taking the entire “row” in stride. He also defended his establishment, arguing that the troublemakers were a minority. “There was rarely any trouble inside the pub,” he stated, adding that “residents rarely appreciate that.” In an earlier interview, he had offered this moment of unexpected levity:

“This is the first disco pub I have run but it is quite enjoyable. Once all this trouble is sorted out I am sure I will enjoy working here all the more.”

The Strange Victory Where the Disco Pub Stayed Open

After months of dispute, the case went before the Greater London Council’s public services entertainments licensing sub-committee. The final newspaper headline announced a bizarre and unsatisfying conclusion for all involved: “VICTORY FOR RESIDENTS – BUT DISCO PUB STAYS”.

The residents had technically won. The council agreed with their complaints and revoked the Red Lion’s music and dancing licence. However, the pub’s owners, Charrington, immediately filed an appeal. This legal maneuver allowed the pub to continue operating as a full-fledged disco for at least another four weeks while the appeal was processed.

This ambiguous result left both sides feeling “disappointed.” For manager Dennis Callaghan, the threat still loomed. For Mr. Percy Whiffin, the win was hollow. Despite the militant talk from some residents, his stated goal had been “to keep the peace” and work towards a “mutual satisfaction for both sides.” The ruling achieved a legal victory but guaranteed that the neighborhood’s fundamental conflict would continue.

Source: blog report generated by Google NotebookLM using scans of editions of the Mitcham and Colliers Wood Gazette.